A week after GE2020, there’s still a bit of chatter regarding the elections. Before I address the problems with first past the post, let’s just look at the results of the elections. There are many websites that have published reliable results to the elections, including Wikipedia. But what I would like to present is, what happens if we use proportional representation instead of the current GRC system. For those who need a refresher, read this article.

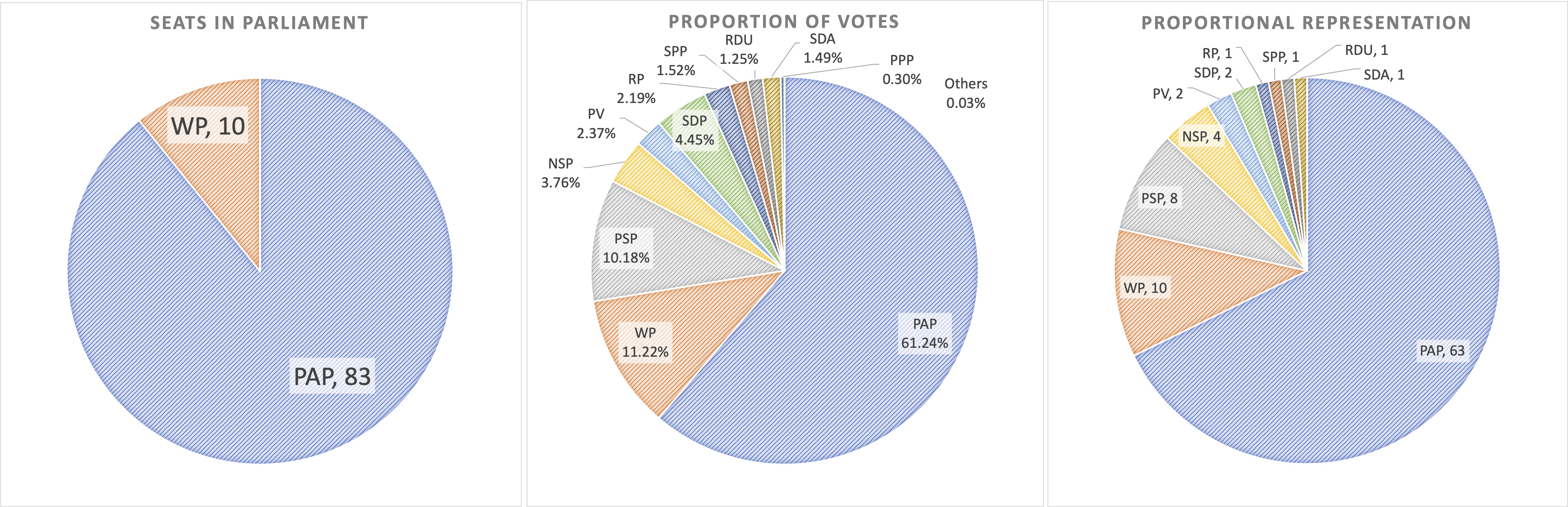

The chart on the left shows how the seats in Parliament (total of 93) are allocated after the elections. The middle chart shows the proportion of votes won by each party and the chart on the right shows the seat allocation if we use a Proportional Representation system.

Now, we see the problems with first past the post (FPTP) voting. But it can get worse. Let’s think about hypotheticals at the moment, where there are just 2 parties. Would you believe me when I say that a party can have a supermajority (2/3 of the seats in parliament) without having 1/3 of the popular vote? Well, in Singapore’s GRC system, it is possible.

Just a bit of background, in the 2020 General Elections in Singapore, the total number of seats available is 93. Thus, to gain a majority, a party needs to win 47 seats and to gain a supermajority (which comes with it the power to change the Constitution), one would need 62 seats. So, suppose I start my own political party, say let’s call it the Joel Lai Party (JLP), what would be my strategy to win the supermajority by winning less than 1/3 of the popular vote? I am about the exploit the flaw in FPTP.

1) Each vote is not worth the same.

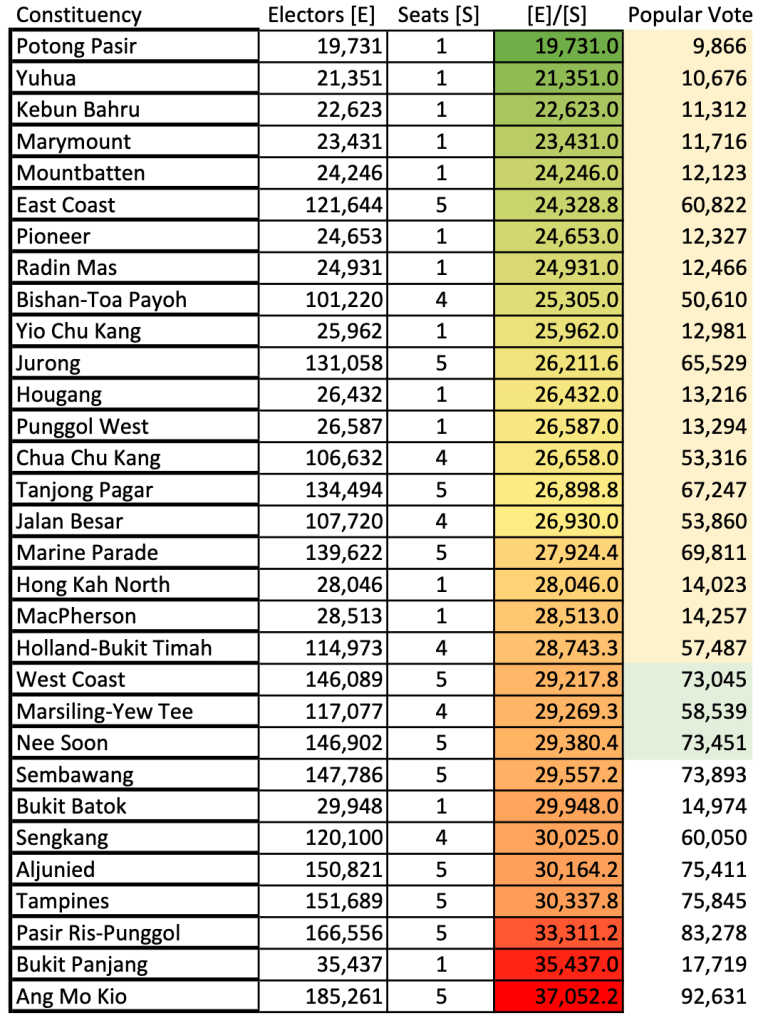

One must first realise that for most forms of democracy, voters are grouped into voting constituencies. In the case of Singapore, we have GRCs and SMCs. Now, because each constituency has a different number of electors (people who cast votes) and seats offered, naturally, it comes with it different weightage to each vote. Let me give you an example. Take Potong Pasir SMC and Ang Mo Kio GRC. Potong Pasir SMC has 19,731 electors and 1 seat up for grab. Ang Mo Kio GRC has 185,261 electors and 5 seats up for grab. What that means is that for each seat allocated to Ang Mo Kio GRC is worth 37,052 votes. Consequently, this means that a vote from Potong Pasir is worth (almost 2 times) more than a vote from Ang Mo Kio. I’ve generated a spread sheet, and you can see how much your vote is worth. The higher you are on the list, the higher the worth of your vote for parliament. JLP will first strategise by finding out the worth of each vote in the different constituencies.

Of course carving constituencies makes sense for better administration, and is inevitable. There are also many other factors to consider. But what we can do is to narrow the worth of each vote. I also noticed that SMCs tend to be worth more than GRCs. I’ll leave that discussion for another time.

2) Targeted campaigning

After recognising that not all votes are worth the same, now is the time to exploit the FPTP system. My strategy is to target the constituencies whose votes are worth more. Since we operate on a FPTP system, we just need to win 50% (+ 1) of the votes. We call this the popular vote. Therefore, by winning the popular vote, I immediately win all the seats available in the constituency. You can see how having multi-cornered fights makes this problem even worse. I now may not need 50% of the votes because, so long as I have the majority out of the multi-party fight, I win the available seat(s). JLP will field candidates and focus our campaign in the constituencies that are worth more, promoting a multi-corner fight, so that it makes our fight easier.

3) Consolidate seats, but not voters

Now, how to I stack the game in my favour? Win the popular votes in the constituencies highlighted in yellow (under the “Popular Vote” column). By winning the bare minimum popular vote in these constituencies, I only gain 23.64% of the total votes, yet, I am able to secure for myself 48 seats, enough to form the majority in parliament. If I am a bit more ambitious, I go on to contest, and win the popular vote in the constituencies highlighted in yellow and green (under the “Popular Vote” column). This time, I gain 31.38% of the total votes, yet, I have 62 seats; just enough to form the supermajority. And of course, it is possible to gain just 50% of the votes in all constituencies, in a 2-party fight, to have 100% control of parliament. Finally, JLP will aim to consolidate seats, but not voters, doing the bare minimum to get me the seats we need. I am now Prime Minister.

To summarise, I am able to secure the majority seat in parliament (and make myself Prime Minister), by winning only 23.64% of the total vote; and secure the supermajority by winning only 31.38% of the total vote. Who does FPTP benefit? It is a remote possibility that JLP or I will be Prime Minister. But the fact that it is even possible in a democracy is in itself bizarre. Now we flip the situation around. It is also possible that the ruling party becomes so unpopular, but they still remain in power if they play the game right and choose to hold the seats as I described above.

FPTP is great for a group of 5 to decide whether to eat HDL or BIAP. But for things like our country, we need Proportional Representation.

One thought on “GE2020: Unrepresentative Democracy (II) Problems with FPTP”