Join me in a simple thought experiment. Imagine you are a standing at a particular position, with a coin in your hand. Every time you flip the coin, the coin (assumed to be fair) shows either tail or head. Your aim is just to move either left or right.

In order to decide whether you move left or right, you flip the coin to decide. After each flip, if the coin is a tail, you take a step to your right; if it shows head, you take a step to your left. After taking the step, you flip the coin again to decide your next step. At the end of 100 coin flips and steps, you take note of your final position relative to your original position (e.g. 4 steps to the left). Now, go back to your original position, repeat the same experiment a million times and take note of the final position of these million times. Where would you expect the average final position to be?

Well, you expect the average final position to be at the original position. At each coin flip, you have equal chance taking a step to the left as to the right. You may have a lucky streak, in one experiment, and have many heads before another tail, but on average, you would expect the reverse case (i.e. many tails before a head) in another experiment. The (fair) coin toss game always gives you an average position of the original position. What happens when we turn the coin into a quantum coin and you into a quantum particle?

Now, the idea of the experiment is the same for the quantum case. However, because this is a quantum experiment, you only have information of what happens at the end of the 100 quantum coin flips. You will knot know anything in between, i.e. the result of each coin toss and, consequently, the direction you move. The weird thing about quantum mechanics is that if you know any information in between, it is equivalent to the original coin toss game. Now, where would you expect your final position to be? If you say the origin, you are not quite right, and that is the weird thing about quantum mechanics.

In the following section, I am going to introduce some maths, if you are not interested, you can skip to the Results section. For those who are mathematically more inclined and have the required concepts from quantum mechanics, here is what happens mathematically:

————— Math Aside —————

Each step of a quantum random walk, U, comprises two transformations.

– the coin flip operator C, and

– the translation operator S, the movement based on the result of the first transformation.

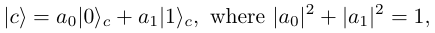

A general 2-sided quantum coin is an arbitrary superposition of two states

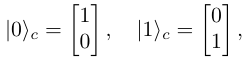

with basis

The first one is equivalent to a head, and the second, a tail. The transformation that we will use to perform the flip is given by the coin operator C which takes the form of a 2×2 unitary matrix:

Notice that there is equal chance of tail or head appearing for the quantum coin. You can see this by looking at the rows of the matrix above, if you take the norm-square of each element of the row vector of the matrix, you get 1/2 (corresponding to probability 1/2 tail and 1/2 head). The position of the walker on the line is represented as a superposition of all the possible states,

with the translation operator S taking the following form:

where s0 and s1 are the number of steps taken by the quantum walker in a quantum walk. Since we want to compare to the original coin toss, if the quantum coin flips a “head” (basis 0), it takes a step s0 = -1 (i.e. a step to the left of its current position); otherwise, if the quantum coin flips a “tail” (basis 1), it takes a step s1 = +1 (i.e. a step to the right of its current position).

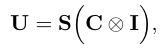

Thus, if we put everything together, the entire transformation, is unitary and combines the coin operator and translation operator, given by

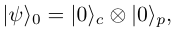

where I is the 2×2 identity matrix. The initial state of the system, in our case, is

alternatively, you can interpret this as equivalent to a quantum walker starting from the position 0. To get 100 steps, we perform the unitary operation on the initial state N = 100 times,

——————————

Result

I wrote a code to run the above mathematics for 100 steps for both the standard coin and the quantum coin. Here are the results:

Interestingly, notice that the average position for the quantum coin flip is not around the original position (set to be 0). Instead, it is skewed to the left. What this means is that somehow, in the midst of flipping the quantum coin and taking steps, the average position is somehow skewed to the left rather than remaining at the original position.

The reason? Quantum mechanics is weird! Well, it can be weird, but can we explain what is going on? Yes. In quantum mechanics, the person performing the walk (which we have assumed to be you), is not in a fixed position every time the coin is flipped. In fact, you can think of the person being at all possible positions at any given time. This idea is called superposition. Consider two water waves. When the waves pass by each other, the waves will interfere with each other. Some parts of the wave will cancel each other, while other parts will amplify each other.

In the same way, for the quantum version of this coin flipping game, the “person” who is flipping the quantum coin is actually a wave. This wave spans all possible positions that the “person” can be in. As the coin is flipped and a “step” is taken, think of this “step” as the wave repositioning itself. As the wave repositions itself, certain positions become inaccessible because the wave cancels its previous self conversely, the wave can be amplified at some positions. This can be proven mathematically, which you can find in my paper.

But this result is stunning. What it tells us is that a fair quantum coin, actually does eventually result in a biased outcome (as long as we do not know what happens in between the coin flips).

Stay tuned for part 2 as we apply this to my research.