Let’s play a game. In this game, we choose a coin to toss. If the coin lands on ‘Head’ you will pay me $1. However, if it lands on ‘Tail’ I will pay you $1.

In the first version of the game (let’s just call it, game A), we have a biased coin. When tossed, the coin lands on ‘Head’ 49.5% of the time and ‘Tail’ 50.5% of the time. Will you play game A with me? It is quite obvious that you should play this game with me! In 1000 games, you would expect to win 505 of them, while I can only expect to win 495 of them. Since you will win 10 more games than me, you would gain an average of $10 in 1000 games. We can simulate this by plotting a graph.

On the y-axis, we plot how your capital changes with each flip. For the graph on the left, it shows one round of 1000 flips. If we were to average this over one million of such games, The fact that it is positive shows that you will emerge a “winner”. Game A is definitely favourable for you. So let’s shake things up a little.

For the second game (Game B), it is slightly more complicated, we now have two biased coins C1 and C2. We decide which coin to flip depending on how much money you have on hand right now.

– If the money you have can divide 3, we choose to flip the first coin C1.

– If the money you have cannot divide 3, we choose to flip the second coin C2.

For coin C1, ‘Head’ appears 9.5% of the time and for coin C2, ‘Head’ appears 74.5% of the time. It is not clear right now whether you should play this game with me. To figure that out, we can plot the same graph as what we did for Game A.

Previously, just base on probabilities, it was not clear if you should play this game with me. But after we plot the graph, we can see that you should play the game with me because you will still end up winning (averaged over one million games).

It now seems that regardless of whether we are playing Game A or Game B, I seem to be on a losing end here. For me, both Games A and B are losing in the long run. Can I do something such that I can win? As it turns out, I can.

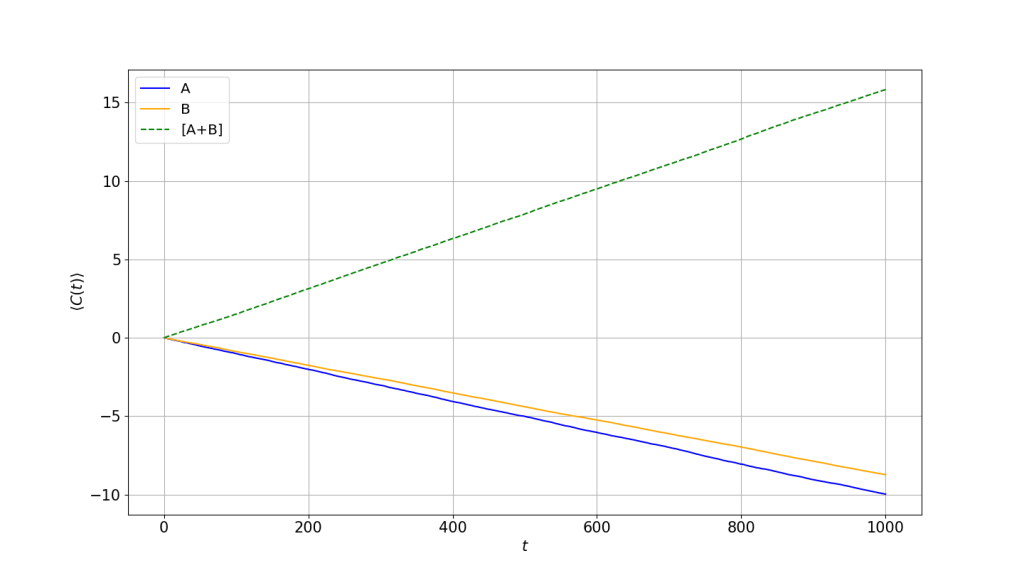

All I have to do, is to randomly decide when to play Game A and B. For example, I can choose to play the game in a random sequence ABAAABBABABBB… , that is a random sequence of 1000 tosses. If we were to average it over a million of such random games, I can take two losing games, combine them in a random fashion and achieve a winning outcome for myself (which means you will end up losing). The graph below shows the expected money I have when playing A and B individually for 1000 tosses and when I randomly choose between games A and B (denoted with [A+B]). The simulation is averaged over a million games.

and a random game [A+B] (green dotted line)

Two losing games combining to give a winning game – this is Parrondo’s Paradox. Can we ever replicate such a thing in a standard casino game? Probably not. What use is there? That’s the point of my research.